Lately, I’ve been talking with a few early career scientists among my friends, trying to convince them to set up a website, and perhaps have some kind of open social media presence (e.g. Twitter.)

The primary reason is that since they’re going to have jobs where they will be judged on their past accomplishment, their names will necessarily be googled, and random results will appear; perhaps linkedin, google scholar, researchgate or a github account will show up on the first result page (try googling your name in private mode!) Having a website would allow to take control of the information about you, and highlight what you think is relevant.

The second reason, and perhaps the most important, is that as scientists we are public intellectual. We are paid to produce research and communicate around it. You are entitled to use your expertise on topics in your field and make it clear, through a webpage or a blog, and maybe share tools and resources you found useful. The scientific publication ecosystem is pretty bad, far from open access, and articles themselves are so terse they cannot be understood by anyone outside your field. You can use your website to make your research publicly available (it’s legal, you still own the rights, see here) and also give some context to it, by surrounding it with other relevant pieces or break it down to make it digestible.Don’t be afraid of the light

However, the typical reaction of my fellow researcher is that “it’s not my style”, “I don’t want to self-promote.” I tend to think it’s oftentimes and extension of the impostor syndrome (great piece by my friend Maria Żurek)

It was about one year ago when I received an email: “Dear Dr. Żurek, We are happy to offer you a postdoctoral position at Berkeley Lab”. And what was my first reaction? “They probably think I’m nice, so they didn’t realize I’m inadequate”. Yes, this was my first thought, even if I had objectively good research experience, even if I was very well prepared for the application, even if I was fully aware that what I had been dealing with was the monster called impostor syndrome.

Since you spend your time doubting about the depth of your knowledge, you can never find the right time to talk about it.

But in truth I believe a big part of it is laziness – or just knowing where to start: it’s not easy to set up a website, though there are helpful guides for those who are interested (e.g. Dan Quintana.)The visibility of scientists

Another important aspect of the scientist as a public individual is to lead by example. Academia is rapidly evolving, and we need to be visible to make everyone welcome. While historically it’s been pretty white, pretty male and pretty old, with a heavy dose of reproduction among elites, it is important to share your own story, as younger scientists may not know how academia works, because their parents or nobody around them were not academics themselves. (alternatively, writing wikipedia pages for others is a good occasion to document such stories, and for you to learn from other people trajectory and pass it on.)

It also became increasingly important that the scientist engages the public sphere. Not only to counter false messages, but also because influential (read: established) scientist also happen to be out of touch.Twitter presence is also good in your pursuit — it’s a good hook if you don’t have the time for a full blog/website and you’re looking for interaction. Here’s a piece on how to get started: Threads. It’s also important to understand the Science Twitter ecosystem; here’s a few account I enjoy which to me represent various aspects of the question- Katie Mack @AstroKatie

- Michael Eisen @mbeisen

- Jess Wade @jesswade

- 〈 Berger | Dillon 〉@InertialObservr

- Gabriel Peyre @gabrielpeyre

- Sarafina Nance @starstrickenSF

- Dan Quintana @dsquintana

Science communication

Let me insist here once again that papers aren’t written to be read, but to be evaluated (eventually, if you land Nature, you’ve scored an A+) and actually very few people will do the promotion of your research (there’s no money to make out of it.) Write a paper is like getting a great, it’s your role to make it accessible. Plus doing this effort at the start will compound — later on you can more easily share research and *its context* with others.

It is good to have some experience with writing non-scientific articles: it pushes you to conduct interviews to substantiate your claims. Asking colleagues is sometimes… anathema in science, for fear of competition. But this is rarely the true excuse: people are often just too lazy to reach out. Teach yourself and your colleagues to do it!In “Between the World and Me”, Ta-Nehisi Coates characterize journalists as seekers, and scientists should also seek to be seekers, and not only through producing new results but also by synthesizing information which is already there or summarizing opinions on a given topic. And that’s an acquired skill you learn by doing, and may help you create fruitful collaborations: the most interesting results often come from serendipitous interactions, and that’s something to cultivate.Polis

Politics is a very sensitive topic in science. People like to think science is neutral, because scientists are seeking some kind of grand objective truth, and that politics has nothing to do with it. In truth, they are afraid (and reasonably so) to get their funding cut. Actually, scientists love to talk about politics, but it barely transpires outside the coffee room.

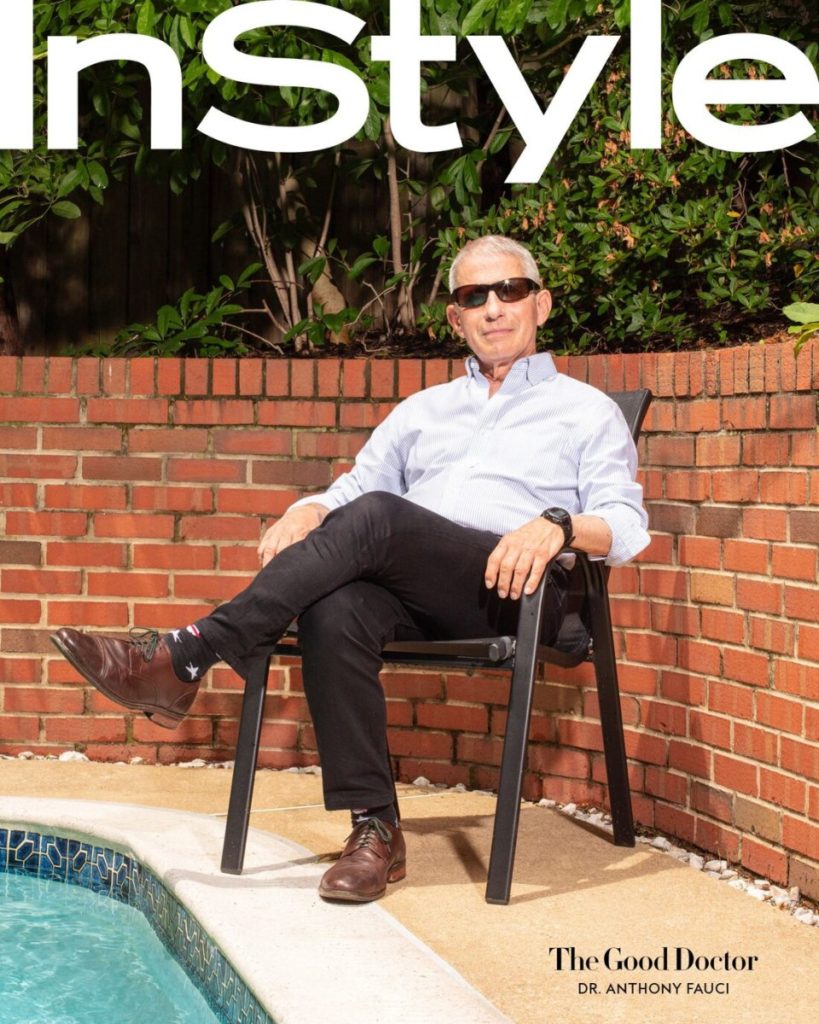

The current period, where the current pandemic of covid-19, and the looming threat of climate change has never made clearer that scientists are under assault and need to speak up. You are entitled to your opinion, and as long as you don’t speak in the name of your institution (and make it clear), things should be fine.Just look at the most prominent scientist of the current era, Anthony Fauci. He doesn’t hesitate to reach out, and he’s perfectly comfortable with that:If he can do it at age 80, why couldn’t you?