Liminary note: I am not a social scientist, but I try to educate myself about some issues facing academia, and this is the result of my inquiries. If you think some elements are incorrect or if you have good resources to share, please let me know!

In this short Life

that only merely lasts an hour

How much – how

little – is

within our

power

–

Emily Dickinson

Gender gaps in academia are pretty dire, and while it seems to get acknowledged and addressed, it’s not clear whether the root causes – especially social norms – are fully understood and can be solved. The paper Understanding persistent gender gaps in STEM (Science 368, 6497; June 2020, pdf) offers interesting statistics and insights.

The problem does not seem to be a difference in achievement, but social factors rather.

I found this part a bit distressingFor high-achieving students, our analyses suggest that efforts to boost women’s PECS aspirations and intentions (i.e., the strongest set of predictors)—such as role-model interventions and Girls Who Code —may work well to eliminate the gender gap in pursuing PECS at the top of the distribution. […] This clearly implies that to close the PECS-pursuit gender gap among the top achievers, the critical piece is in converting all other STEM-positive factors (e.g., confidence and interest) into actual aspirations and intentions. Unfortunately, for average- and low-achieving students, our analyses also revealed that the field’s understanding of how to get average- and low-achieving girls into the field is more limited. The same factors that explained the PECS gender gap at the top of the distribution collectively explained less and less of the gap further down the distribution. Thus, the interventions that may work for high-achieving girls are unlikely to work for lower-achieving ones. Moreover, focusing efforts on attracting high-achieving women to PECS may back-fire: Whereas men have male peers to serve as role models throughout the achievement distribution, having only high-achieving role models for women may send signals to average- and low-achieving women that they do not have the necessary STEM skills to succeed (see SM, section 4).

I admire the effort of many to improve representation on wikipedia matters a lot, for it helps already successful women scientists regain the place they deserve, but we must make sure not to see. The same things go for “women panels”, where the you-can-have-it-all stance may send the wrong signal (in addition to other issues such related the academic Bechdel test.) From Pérola Milman’s “Ceci n’est pas une femme : La Jeune fille, le Trou noir et la Mort” (translation coming soon):

One thing leading to another, telling us about our respective frustrations and small rewards in each of the activities mentioned and in so many others, we end up asking ourselves – me to her, her to me – almost in unison: “but have you seen the last CNRS newspaper? ”. And we burst out laughing, together! Yes, we both saw it. And that’s why we particularly felt particularly like shit that day. The last issue of the newspaper gave us a portrait. A portrait of a woman. Of a woman who really exists. A woman called “the boss” in the newspaper. A woman covered in prizes, almost a professional musician, mother of six, slim, smiling, and who said “that her status as a woman has never been a handicap” and “doing research is not easier for boys than for girls ”. A remarkable person, without a shadow of a doubt. And seeing this fabulous, brilliant person, my friend and I, we immediately saw each other shine, too. But what shone, what stood out, were our disabilities. The holes in us. Our holes, although black, shone brightly. Indeed, this portrait confirmed that our feeling of spending a lifetime rowing – and worse: rowing without direction – may not have just been an impression.

What happens in Scandinavian countries is interesting:

The ‘paradox’ of working in the world’s most equal countries (BBC)In politics, 46% of Swedish members of parliament are women, while the proportion in other Nordic countries is around 40%.

However, there are still surprisingly few women in senior private sector roles. Just 28% of managers in Denmark are female, rising to 32% in Finland and Norway, and 36% in Sweden, according to a report by independent think tank The Cato Institute in 2018.

and later trying to find an explanation:

Last year, researchers in the US and UK found that countries with an existing culture of gender equality have an even smaller proportion of women taking degrees in science, technology and mathematics (STEM).

“It is a paradox … nobody would have expected this to be the reality of our time,” says Professor Gijsbert Stoet, one of the report’s authors.He argues that since Nordic countries have a generally high standard of living and strong welfare states, young women are free to pick careers based on their own interests, which he says are often more likely to include working in care-giving roles or with languages. […]“Girls and boys are different, and have different preferences on the whole,” he argues. He believes too much media focus is placed on the lack of women in CEO positions, since these account for such a small proportion of jobs overall, and suggests that more men fill these roles since “the personality traits and ambition to be important and famous is higher in men than women”.But others strongly believe that social conditioning is the major driver when it comes to women’s career choices and promotion opportunities, and stress that gender stereotypes persist.“I don’t think it’s about choice, it’s about structures … to say it’s about choice is to ‘blame the victim’,” says Anneli Häyren at the Centre for Gender Research at Uppsala University.

It seems the issue will not vanish through some flavor of affirmative action (even if useful), but by questioning society as a whole and rewriting some of its rules – though the best approach is not clear.

Social construct

An friend of mine, who immigrated from Iran many years go was telling me how women in Iran, despite an oppressive regime, manage to outperform men in STEM fields, perhaps because the highest positions in politics are barred from them, and that science, being somewhat objective, allows them to avoid some of the traps put in front of them.

The most striking example of this is Maryam Mirzakhani, the only women to be awarded a Fields medal and whose life is depicted in the excellent Secret of the Surface. When she died of cancer at age 40 a few years ago, she became the first women appearing on the front page of Iranian newspaper without a veil.Another anecdotal evidence is the apparent increase of interest for science in all-girls school, especially in the British islands, where competition between boys and girls is nonexistent, the social factors therefore obeying to different rules.But it’s clear that going to these extremes to close the gap is not an option (and a particularly bad idea.)Branches of the same tree

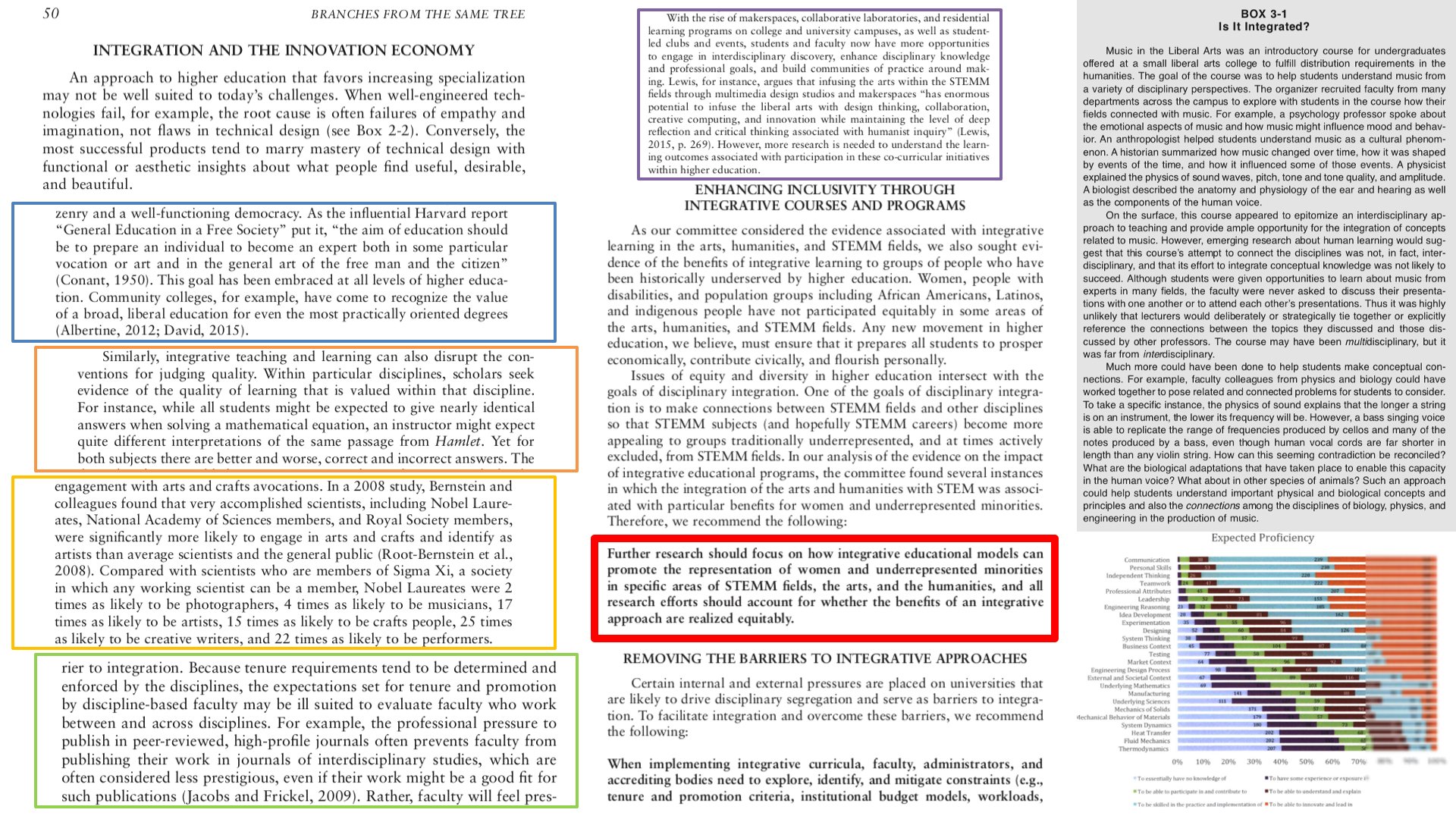

Since there is somehow parity at the top but not in the bulk of students, it might be worth consider other avenues to attract women to science. An interesting option to consider is to blend science and arts, with the hope of breaking the walls. The report of the National Academy of Science “The Integration of the Humanities and Arts with Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine in Higher Education” (free to download after registration) offers some insights. Here are my reading notes:

Previous articles on the topic of gender in academia

Previous articles on the topic of gender in academia

edit October 6, 2020: I’m extremely glad Andreas Ghez got awarded the Nobel prize for her work. Incidentally, I’ve learned about the Finkbeiner Test, the equivalent of the Bechdel Test in academia. Fasten your seat belts, you will hear many violations in the next few weeks…

The new Nobel laureate in physics, Andrea Ghez, indirectly inspired an important test in science writing, the “Finkbeiner Test,” created to help reporters avoid gender bias. To pass this test….1/7

— Nell Greenfieldboyce (@nell_sci_NPR) October 6, 2020