My friend Sana has started a wonderful literary project called “A known space.”

Here’s the first issue: A known space: Vol. 1: Nucleus (my personal contribution: The Sound of the waves)

credit: Szymon Kobusiński – TRANSSUBSTANTIATIO

Wade on!

My friend Sana has started a wonderful literary project called “A known space.”

Here’s the first issue: A known space: Vol. 1: Nucleus (my personal contribution: The Sound of the waves)

credit: Szymon Kobusiński – TRANSSUBSTANTIATIO

Wade on!

The past nine months have been spent working from home, and it has now become clear that what I miss the most is the casual interactions with colleagues in the coffee room.

It is a place where ideas sparks, and where information flows from one scientist to the other. The importance of this liminal space should not be understated. It provides a safe space where ideas can be freely challenged and developed, owing to the generally low number of participants, the low stakes and the general mood.Over the years, I’ve developed several coffee clubs in my buildings (I’ve changed buildings three times), adding an espresso machine wherever I could (often on my own funds, though coffee beans where purchased collectively.)

Elementary Table of Coffee (Berkeley Lab building 2 coffee room, 2013-2016) (@awojdyla, Feb 4 2018)

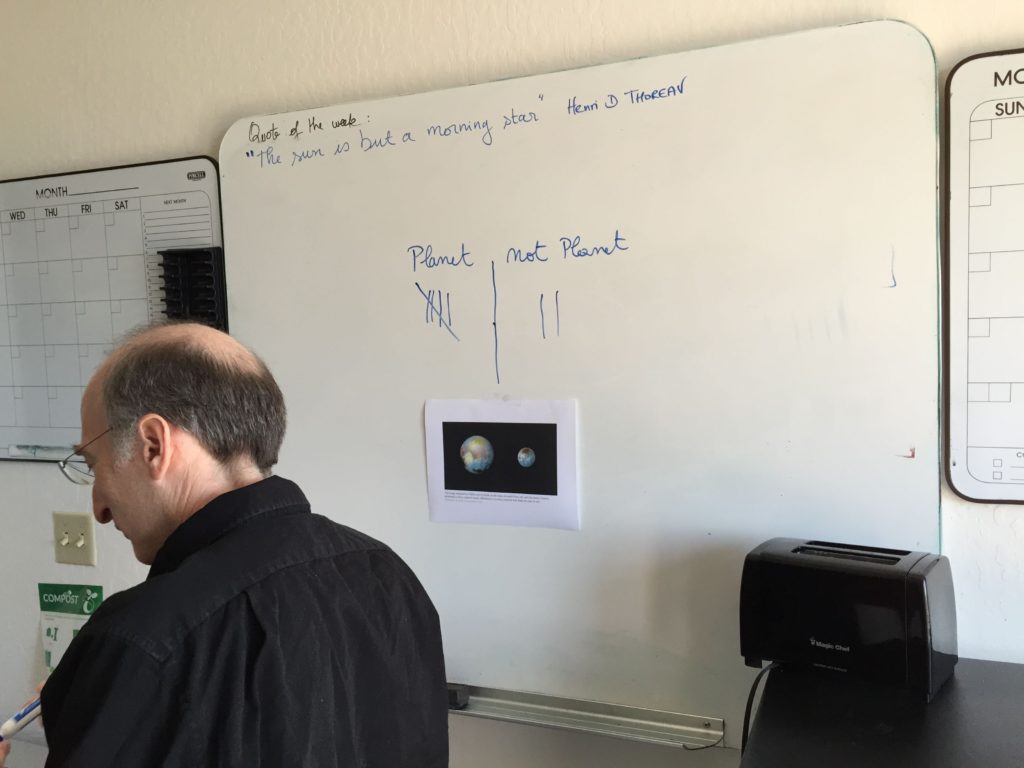

The importance of the mood component became apparent as we switched to online meetings and we started to lack this kind of space (thankfully my colleague Diane B. organized regular coffee zooms!), though nothing replaces the in-person interaction, with a white board where people can share their thoughts.

Saul Perlmutter casting a definitive vote on the planet-ness of Pluto in our coffee room (Berkeley Lab building 2)

Lately, I’ve been talking with a few early career scientists among my friends, trying to convince them to set up a website, and perhaps have some kind of open social media presence (e.g. Twitter.)

The primary reason is that since they’re going to have jobs where they will be judged on their past accomplishment, their names will necessarily be googled, and random results will appear; perhaps linkedin, google scholar, researchgate or a github account will show up on the first result page (try googling your name in private mode!) Having a website would allow to take control of the information about you, and highlight what you think is relevant.

The second reason, and perhaps the most important, is that as scientists we are public intellectual. We are paid to produce research and communicate around it. You are entitled to use your expertise on topics in your field and make it clear, through a webpage or a blog, and maybe share tools and resources you found useful. The scientific publication ecosystem is pretty bad, far from open access, and articles themselves are so terse they cannot be understood by anyone outside your field. You can use your website to make your research publicly available (it’s legal, you still own the rights, see here) and also give some context to it, by surrounding it with other relevant pieces or break it down to make it digestible.However, the typical reaction of my fellow researcher is that “it’s not my style”, “I don’t want to self-promote.” I tend to think it’s oftentimes and extension of the impostor syndrome (great piece by my friend Maria Żurek)

It was about one year ago when I received an email: “Dear Dr. Żurek, We are happy to offer you a postdoctoral position at Berkeley Lab”. And what was my first reaction? “They probably think I’m nice, so they didn’t realize I’m inadequate”. Yes, this was my first thought, even if I had objectively good research experience, even if I was very well prepared for the application, even if I was fully aware that what I had been dealing with was the monster called impostor syndrome.

Since you spend your time doubting about the depth of your knowledge, you can never find the right time to talk about it.

But in truth I believe a big part of it is laziness – or just knowing where to start: it’s not easy to set up a website, though there are helpful guides for those who are interested (e.g. Dan Quintana.)Another important aspect of the scientist as a public individual is to lead by example. Academia is rapidly evolving, and we need to be visible to make everyone welcome. While historically it’s been pretty white, pretty male and pretty old, with a heavy dose of reproduction among elites, it is important to share your own story, as younger scientists may not know how academia works, because their parents or nobody around them were not academics themselves. (alternatively, writing wikipedia pages for others is a good occasion to document such stories, and for you to learn from other people trajectory and pass it on.)

It also became increasingly important that the scientist engages the public sphere. Not only to counter false messages, but also because influential (read: established) scientist also happen to be out of touch.Twitter presence is also good in your pursuit — it’s a good hook if you don’t have the time for a full blog/website and you’re looking for interaction. Here’s a piece on how to get started: Threads. It’s also important to understand the Science Twitter ecosystem; here’s a few account I enjoy which to me represent various aspects of the questionLet me insist here once again that papers aren’t written to be read, but to be evaluated (eventually, if you land Nature, you’ve scored an A+) and actually very few people will do the promotion of your research (there’s no money to make out of it.) Write a paper is like getting a great, it’s your role to make it accessible. Plus doing this effort at the start will compound — later on you can more easily share research and *its context* with others.

It is good to have some experience with writing non-scientific articles: it pushes you to conduct interviews to substantiate your claims. Asking colleagues is sometimes… anathema in science, for fear of competition. But this is rarely the true excuse: people are often just too lazy to reach out. Teach yourself and your colleagues to do it!In “Between the World and Me”, Ta-Nehisi Coates characterize journalists as seekers, and scientists should also seek to be seekers, and not only through producing new results but also by synthesizing information which is already there or summarizing opinions on a given topic. And that’s an acquired skill you learn by doing, and may help you create fruitful collaborations: the most interesting results often come from serendipitous interactions, and that’s something to cultivate.Politics is a very sensitive topic in science. People like to think science is neutral, because scientists are seeking some kind of grand objective truth, and that politics has nothing to do with it. In truth, they are afraid (and reasonably so) to get their funding cut. Actually, scientists love to talk about politics, but it barely transpires outside the coffee room.

The current period, where the current pandemic of covid-19, and the looming threat of climate change has never made clearer that scientists are under assault and need to speak up. You are entitled to your opinion, and as long as you don’t speak in the name of your institution (and make it clear), things should be fine.Just look at the most prominent scientist of the current era, Anthony Fauci. He doesn’t hesitate to reach out, and he’s perfectly comfortable with that:If he can do it at age 80, why couldn’t you?

Liminary note: I am not a social scientist, but I try to educate myself about some issues facing academia, and this is the result of my inquiries. If you think some elements are incorrect or if you have good resources to share, please let me know!

In this short Life

that only merely lasts an hour

How much – how

little – is

within our

power

–

Emily Dickinson

Gender gaps in academia are pretty dire, and while it seems to get acknowledged and addressed, it’s not clear whether the root causes – especially social norms – are fully understood and can be solved. The paper Understanding persistent gender gaps in STEM (Science 368, 6497; June 2020, pdf) offers interesting statistics and insights.

The problem does not seem to be a difference in achievement, but social factors rather.

Continue reading(I owe this piece to a conversation with Laleh Coté – she’s doing an incredible job on STEM mentorship, and even in these difficult times, she documents her observations on how it impacts these efforts.)

I’m always happy to mentor students, for it gives you a change to light a candle, but also forces you to explain things in a legible way – and if you can’t perhaps you don’t really understand things yourself.Berkeley Lab has a great program for interns, and it comes with some resources: WD&E Mentor Handbook (pdf)Because of the pandemic, all the summer internships have morphed into virtual internship. While everyone is still trying to figure out how to make it work best, some initial best practices where collected here: Virtual Remote Mentor Guide -DOE-SC-WDTS Programs- May 2020 (pdf)Nowadays, many conferences and workshops are going online because of the pandemic, and we all are ill-prepared for this kind of shift forced upon us. Delivering an online presentation is very different from delivering an in-person presentation, for a few reasons, and we need cognizant of the nuances.

While many talks are indeed disastrous (people lack proper training), going to a conference is often not only about the content of the talks (you could just read the papers), but about visual and vocal cues which are often absent from literature. These cues help you figure out what are the important points and make clear what what other people are interested in.Therefore, it is important to establish and maintain contact with the audience. For this, there are many things we can learn from news anchor: they also talk to the camera, they have dedicated studios and they alternate between speaking and news content.I attended an online workshop by Jean-Luc Doumont on delivering an online presentation, and I found it useful. Here are some of my takeaways. Continue readingLet us represent a dot by a small spot of one metal, the next dash by an adjacent spot of another metal, and so on. Suppose, to be conservative, that a bit of information is going to require a little cube of atoms 5 x 5 x 5 – that is 125 atoms. Perhaps we need a hundred and some odd atoms to make sure that the information is not lost through diffusion, or through some other process.

– Richard Feynman

Spoiler alert: we are nearly there!

* *

These very old line (1959) fro Feynman’s famous speech “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom” is still valid, though nowadays are getting very close to the bottom!With my colleague Gautam Gunjala, we published an article in Berkeley Science Review on the ongoing contributions of UC Berkeley and Berkeley Lab to photolithography, the process of making microchips: Room to Shrink.It was supposed to be part of the BSR Issue 38 (Spring 2020) but I guess it got covided.

Here are other pieces from yours truly on the topic:Also:

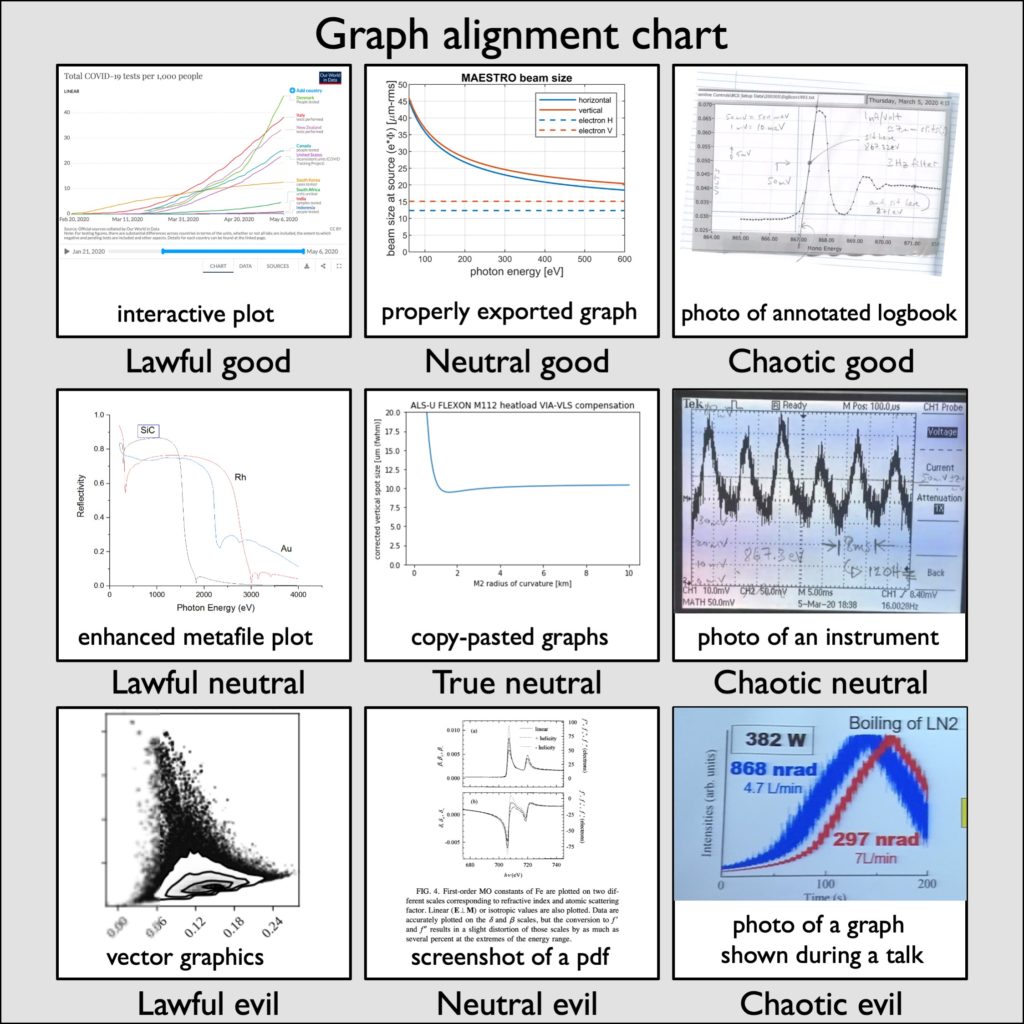

The topic is getting red hot politically:There are many ways to document research, and some are better than others.

Make beautiful graphs : only start to write when you have the best data our group can get.

– Paul Alivisatos

Here’s my graph alignment chart, curated from personal experience.

Continue reading

Continue reading

Today is Earth Day, a celebration of Earth and the environment started fifty years ago. This year, as the covid-19 pandemic upends the regular unfolding of the world, we can step back and ask how what we learn from the current crisis can help us scientists make science better and more efficient to curb climate change and its consequences.

Here’s a set of eight question to ponder about this, and some preliminary thoughts gleaned during a forum@ESA.1. The interdependence of the supply chain has become very apparent. Can we make the case for renewable energy in terms of resilience of systems?Solar energy is the only form of energy available everywhere on the planet: all others need to be transported and transferred. Geothermal energy should also be tapped (it is essentially low grade solar energy!)2. The dramatic reduction of activity in urban centers has brought back clean air in some cities for the first time in decades. Can we envision a world without emission, from energy production to energy use?Cars on the road have the most impact – we need to switch to switch transportation modes. We could have electrical energy on tracks, some flavor of autonomous driving could quickly provide modular transportation schemes. We also need to change how some cities are built, to make it easier to have common transportation (relative location of schools, business and housing)3. The current covid-19 crisis is global, and scientists have broken paywalls and started new collaborations with their peers around the globe. What can we learn from this, and promote meaningful collaborations?Open Access is on the rise (Project DEAL, Plan S, White House Open Access plan.) Wikipedia is a great resource, completely under-used; it seems that it stems from the issue of ownership (who gets to write on who? and who gets the credit for this work?) We can also rethink research tools, to make them more efficient and more collaborative. The way academia is organized (race to tenure, etc.) may hamper collaboration and therefore innovation.4. The global economy has been hit severely, and it will be important to promote new economic activity when the outbreak will be over. How can energy technologies inform policies and shape capital projects?We could build mass transportation system, with initiatives similar to the New Deal (infrastructure is manual labor intensive.) Science can help to find which are the most effective or efficient ways (data science and machine learning.) Scientists could work in tandem with civil engineers, maybe using their school network to reconnect. There should be incentives for scientists to do so.5. The disruption school year has taken a toll on kids and parents alike. How can scientists engage with students, when the distance is measured in bits per seconds rather than miles?It would be good to reuse and repurpose older devices. There could be an open OS for discarded devices that would provide minimal functions (video conferencing, calculator, etc.) Scientists should also learn to mentor without physical presence (though one-on-one interaction is important), and therefore allow more frequent interactions, over larger distances.6. When resources are lacking – masks, ventilators,– engineers and scientists devise creative ways to fill the need using available resources and altering them. How could we repurpose existing facilities to help with climate change?7. The shelter-in-place is difficult to negotiate, but as anthropogenic emission of CO2 affects the environment, it may become routine. How can we fix the harm done using science and technology?8. There is a lot of contradictory information being circulated around the epidemic. How can scientists help disseminate information and prevent the spread of alternative facts? In addition, here are some historical and current resources on Climate Change:

Here’s a set of eight question to ponder about this, and some preliminary thoughts gleaned during a forum@ESA.1. The interdependence of the supply chain has become very apparent. Can we make the case for renewable energy in terms of resilience of systems?Solar energy is the only form of energy available everywhere on the planet: all others need to be transported and transferred. Geothermal energy should also be tapped (it is essentially low grade solar energy!)2. The dramatic reduction of activity in urban centers has brought back clean air in some cities for the first time in decades. Can we envision a world without emission, from energy production to energy use?Cars on the road have the most impact – we need to switch to switch transportation modes. We could have electrical energy on tracks, some flavor of autonomous driving could quickly provide modular transportation schemes. We also need to change how some cities are built, to make it easier to have common transportation (relative location of schools, business and housing)3. The current covid-19 crisis is global, and scientists have broken paywalls and started new collaborations with their peers around the globe. What can we learn from this, and promote meaningful collaborations?Open Access is on the rise (Project DEAL, Plan S, White House Open Access plan.) Wikipedia is a great resource, completely under-used; it seems that it stems from the issue of ownership (who gets to write on who? and who gets the credit for this work?) We can also rethink research tools, to make them more efficient and more collaborative. The way academia is organized (race to tenure, etc.) may hamper collaboration and therefore innovation.4. The global economy has been hit severely, and it will be important to promote new economic activity when the outbreak will be over. How can energy technologies inform policies and shape capital projects?We could build mass transportation system, with initiatives similar to the New Deal (infrastructure is manual labor intensive.) Science can help to find which are the most effective or efficient ways (data science and machine learning.) Scientists could work in tandem with civil engineers, maybe using their school network to reconnect. There should be incentives for scientists to do so.5. The disruption school year has taken a toll on kids and parents alike. How can scientists engage with students, when the distance is measured in bits per seconds rather than miles?It would be good to reuse and repurpose older devices. There could be an open OS for discarded devices that would provide minimal functions (video conferencing, calculator, etc.) Scientists should also learn to mentor without physical presence (though one-on-one interaction is important), and therefore allow more frequent interactions, over larger distances.6. When resources are lacking – masks, ventilators,– engineers and scientists devise creative ways to fill the need using available resources and altering them. How could we repurpose existing facilities to help with climate change?7. The shelter-in-place is difficult to negotiate, but as anthropogenic emission of CO2 affects the environment, it may become routine. How can we fix the harm done using science and technology?8. There is a lot of contradictory information being circulated around the epidemic. How can scientists help disseminate information and prevent the spread of alternative facts? In addition, here are some historical and current resources on Climate Change:

I also made a thread about Berkeley Lab Art Rosenfeld on his Art of Energy Efficiency.

Continue readingOver the last two years, I had a chance to visit a few synchrotron around the world!

Here’s my fav list:Now I need to visit:

SOLEIL synchrotron (near Paris, France)

SOLEIL synchrotron (near Paris, France) Swiss Light Source (Paul Scherrer Institute, near Zurich)

Swiss Light Source (Paul Scherrer Institute, near Zurich) Taiwan Photon Source (Hsinchu, Taiwan)

Taiwan Photon Source (Hsinchu, Taiwan) Elettra sincotrone (Trieste, Italy) – with Luca Gregoratti

Elettra sincotrone (Trieste, Italy) – with Luca Gregoratti Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory (near Chicago, IL) – with Gautam Gunjala (UC Berkeley)

Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory (near Chicago, IL) – with Gautam Gunjala (UC Berkeley) Advanced Light Source Lawrence Berkeley National Lab (near San Francisco, CA) – with Claudi Mazzoli (from NSLS-II, Brookhaven)

Advanced Light Source Lawrence Berkeley National Lab (near San Francisco, CA) – with Claudi Mazzoli (from NSLS-II, Brookhaven)